Uplifting the Botanical Industry

by Ann Armbrecht

In the American Botanical Council’s Sustainable Herbs Program Ethnobotany Webinar Series, I have been speaking with leading ethnobotanists about their work and especially about what they have learned about the ways culture shapes a community’s interactions with plants. Culture can mean different things. In this case it refers to the frameworks governing how we interact with our world, the invisible tissue that shapes what we do and do not do, what we see and do not see.

In the webinar, “Our Plant Relatives,” with ethnobotanist Leigh Joseph (Styawat), ethnobotanist Nancy Turner spoke about indigenous ways of knowing about plants with those of western science. Scientific frameworks focus on the information about the plants, their characteristics, where they live, when to harvest, etc., which maps well with indigenous knowledge. For indigenous people, she explains, there are other aspects beyond just the knowledge itself, the values and worldviews that you bring to that knowledge. These values govern our actions, placing a limit, perhaps, on how much we harvest or when. They provide a set of practices and actions we should take when we do harvest, offering something in exchange, saying thanks, practices outlined in what Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of Braiding Sweetgrass, refers to as the honorable harvest.

Kincentricity

These practices are encompassed in the idea that everyone is kin, what cultural specialists and ethnobotanists Enrique Salmon and Dennis Martinez call kincentricity—the belief that everything around you is your relative. When you enter the forest you greet the trees as you would a sibling or uncle or child, she explained. You are surrounded by kin. This relationship changes how you interact with those trees. As Turner said, “We wouldn’t think of going into our grandmother’s living room and trashing it. But we do that all the time with the homes of our relatives out there, in the forest.”

Joseph elaborated, “When you shift from looking at a western red cedar tree as a resource with some kind of worth in a monetary sense to thinking about that tree as a relative, the relationship changes. All of a sudden there is an element of reciprocity. I ask different questions: How am I in relationship with this relative? If this relative is interacting with me, and offering me something, what is it that I offer in return? Is it care of the environment that this relative relies on? If I’m harvesting from this relative, how do I do that in a respectful and mindful way to think about the ongoing life of this tree?”

Relationships of Reciprocity and Care

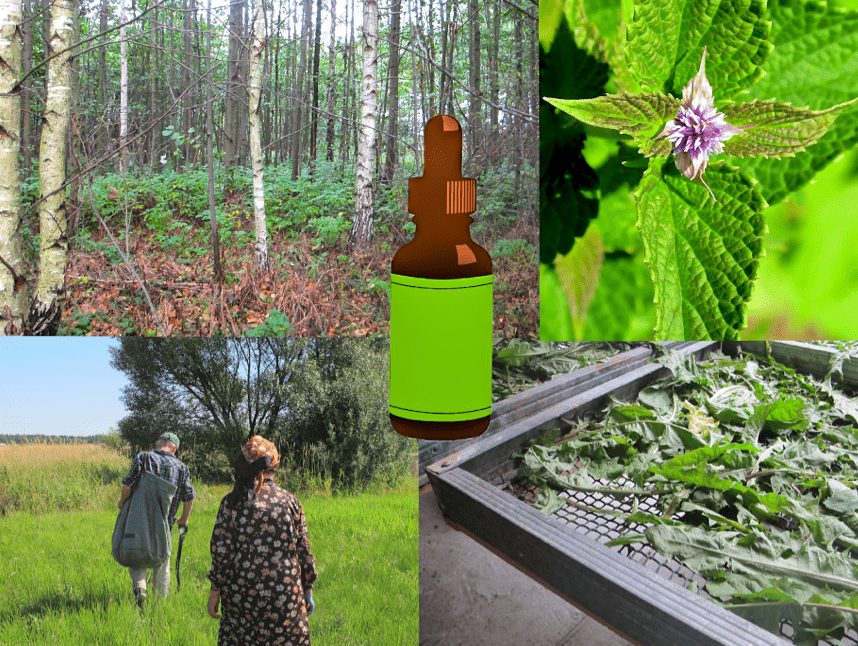

I often begin talks about the American Botanical Council’s Sustainable Herbs Program with this image of a one-ounce tincture bottle suspended in a white background. I ask the audience to pause and consider what they notice, what questions this bottle raises.

Next, I share an image of that same tincture bottle, this time set against images of plants, the forest, wild harvesters. I ask them what questions this image evokes. Try it. The difference can be profound.

When I see that bottle against the white background, I think about its contents and their impact on me, whether what is inside that bottle will do what I hope it will do.

When I instead see the bottle against a backdrop, I am reminded that that product came from somewhere. A relationship, albeit a tiny thread of one, is created to the worlds behind that finished product. Something in me shifts. It is no longer only about my health and my body and my concerns. Even if I only care about that larger context because I see that those worlds behind the product will impact my health and my body, that awareness, perhaps, can be the kernel of an ethics of reciprocity and care.

That relationship to me is the foundation for the different qualities of relationship that Nancy Turner, Leigh Joseph, and many others with whom I have spoken describe. While they are speaking of these qualities in the context of indigenous communities, the feelings they describe aren’t unique to these communities.

We all have the capacity for developing relationships of reciprocity and care.

Is Love Possible on a Global Scale?

We bring these feelings to the things we love, and these feelings in turn create a framework for our actions, practices of respect and restraint, limits to what we do. Everyone has a place that they love, a plant, a person, a corner of a backyard, the bend in a creek. Perhaps the distinction is not whether we have the capacity to live in a world that is our relative. It is whether we bring that self to our intention and attention as consumers.

My goal in hosting this webinar series as it relates to sustainability in the botanical industry is to share stories of other ways of interacting with plants and people. Can we find these modes of interaction in an industry rooted in the buying and selling of medicinal plants from around the world?

As I listen to the speakers, I keep wondering whether love possible on a global scale? If so, where can we find it? In my experience following herbs through the supply chain, the interactions that give me hope are those where people care for more than the bottom line—where they take actions that consider the context, where a framework of ethics and values guides the choices and decisions they make.

As Randy Buresh of Oregon’s Wild Harvest said one sunny morning when we joined him watching his son, who jointly manages the farm with him, harvest their certified organic valerian root from their fields in western Oregon, “It is all about love, doing it from the heart, not doing it from the mind. And that’s a completely different aspect, when you think about it.”

Comments